Kubernetes Reserved Instances: Cost Optimization & FinOps Best Practices

If you deploy Kubernetes in the cloud, the single largest expense associated with your cluster is, in most cases, the cost of cloud servers. Server instances from Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) providers like Amazon EC2 or Azure Virtual Machines cost money. The more you pay for your cloud servers, the more you pay overall for your Kubernetes cluster.

Fortunately, by taking advantage of Kubernetes reserved instances - meaning cloud servers that are available at discounted prices - you can lower total Kubernetes operating costs dramatically.

Read on for guidance as we explain how reserved instances can help enable effective Kubernetes cost management and FinOps, when to use them, and best practices for working with reserved instances as part of your Kubernetes infrastructure.

What are Kubernetes reserved instances, and how do they support FinOps?

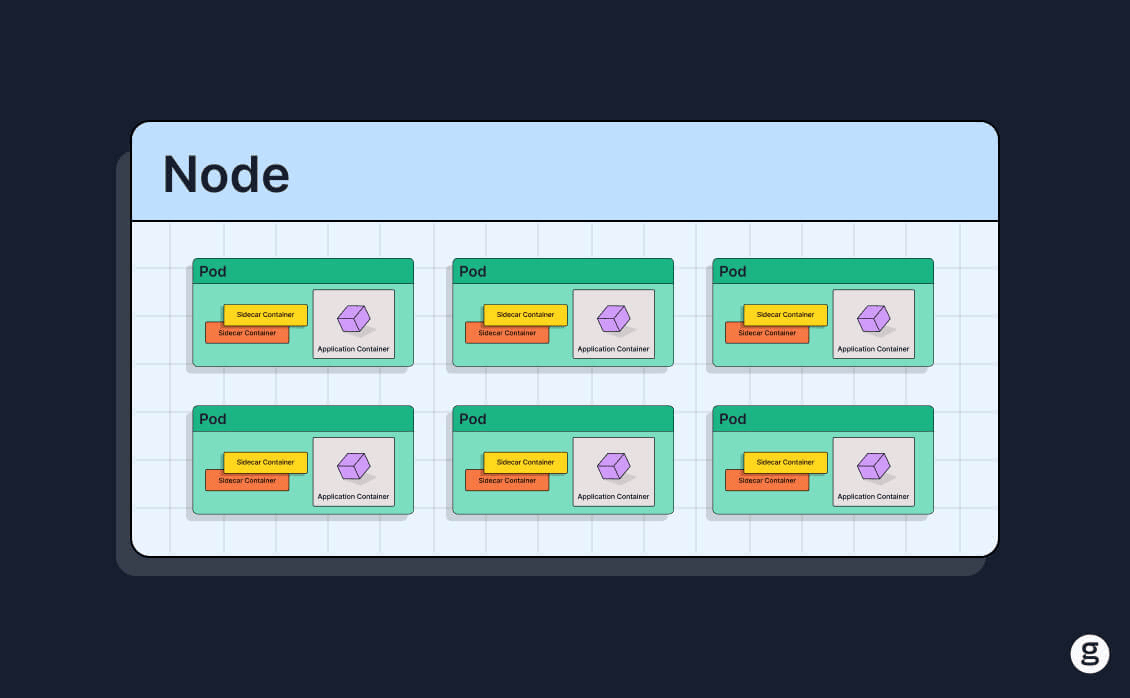

Kubernetes reserved instances are nodes within a Kubernetes cluster that are created using “reserved” cloud server instances.

A reserved cloud server instance is a cloud server that you agree to rent for a specified period of time (usually at least a year). In exchange for that commitment, cloud providers offer discounted pricing on reserved instances. The savings vary, but the cost of reserved instances can be as much as about 70 percent lower than a standard, non-discounted cloud server instance (also known as an on-demand instance). So, when you set up a Kubernetes reserved instance, you rent a cloud server for a specified period of time, then join that server to your Kubernetes cluster as a node.

The savings provided by Kubernetes reserved instances can help businesses achieve cloud cost optimization - the goal of a discipline known as FinOps. Over the past several years, FinOps practices have become increasingly influential as a way for organizations to avoid unnecessary spending in the cloud without compromising on performance or scalability.

Reserved instances vs. committed use discounts

Note that the term reserved instance is associated most closely with Amazon Web Services (AWS), which uses it to describe discounted servers available through its EC cloud server service. Other cloud providers use different terms; the equivalent of reserved instances on Google Cloud is committed use discounts, and the Azure terminology is reserved VM instances in most cases.

That said, reserved instances can be used as a generic term that refers to any cloud server instance that offers discounted pricing in exchange for a long-term use commitment, hence why it’s the term we use in this article.

Reserved instances vs. spot instances

Reserved instances are not the only type of discounted cloud server instance. Another way to save money is to use spot instances. These are available at discounts that are often even steeper than those of reserved instances.

The caveat with spot instances, however, is that the cloud provider can revoke them (meaning they’re no longer available to the customer to use) at any time and without advance notice. This makes spot instances unsuitable as Kubernetes nodes in most cases because you typically wouldn’t want one of your nodes to stop running suddenly.

Thus, if you want to save money on Kubernetes nodes, you’d use a reserved instance rather than a spot instance in most cases. A spot instance would only make sense if your node will host a workload (like training a machine learning model) that can tolerate sudden disruptions or frequent stop-restart events.

Why use reserved instances for Kubernetes? Key benefits

The simple explanation of why to use reserved instances in Kubernetes is that they save money. But there’s more to it than that. Reserved instances provide several key benefits:

- Significant cost savings: As noted above, reserved instances can save as much as 70 percent on cloud server costs, as compared to using standard, on-demand instances.

- Same performance: When you choose a reserved instance, you get the same compute and memory resources as you would from an equivalent on demand instance, so you’re not sacrificing performance.

- Predicability: Because you commit to using reserved instances for a fixed period of time, they offer a consistent, predictable way to provide server resources to a cluster.

The only major drawback (which we’ll discuss in more detail below) is that reserved instances require you to commit to using a cloud server for a fixed period. If you end up not needing it that long, you could lose money. But reserved instances can be a great savings opportunity as long as your long-term Kubernetes infrastructure requirements are predictable.

How reserved instances work in Kubernetes

Kubernetes reserved instances work in the same way as any other server that operates as a Kubernetes node. The only difference is that, with a reserved instance, the cloud server on which a node is based comes with lower pricing.

Note as well that there’s nothing stopping you from using reserved instances alongside other instances within the same Kubernetes cluster. You could, for example, deploy reserved instances to cover the minimum number of nodes you expect to require for your cluster over the long term. At the same time, you could use on-demand instances to meet temporary increases in Kubernetes infrastructure requirements. This would allow you to minimize overall Kubernetes infrastructure costs while retaining flexibility and scalability.

Setting up reserved instances in Kubernetes

The process for setting up Kubernetes reserved instances is as follows.

Deploy a reserved instance

First, create a reserved cloud server instance using a cloud IaaS service (such as Amazon EC2, Azure Virtual Machines, and Google Cloud Compute Engine). The exact steps for doing this vary depending on which IaaS platform you are using. But in most cases, you can simply log into the cloud provider’s console, navigate to the IaaS server, and choose reserved instances to deploy.

Note that most IaaS services provide a wide range of instance types. Each type includes different levels of compute and memory resources (some include additional hardware features, like GPUs), and is available at different price points. But from the perspective of Kubernetes reserved instances, it doesn’t matter which instance type you choose, so long as you select one that is available under a reserved instance pricing plan.

Start the reserved instance

After creating a reserved instance, you have to start it in most cases (with some IaaS services, it may launch automatically). This is an important step because you can’t complete the next step until your server is up and running.

Join the server to your Kubernetes cluster

Once the reserved instance has booted (which may take up to a couple of minutes), join it to your Kubernetes cluster.

Here again, the exact process can vary depending on which Kubernetes distribution you’re using. But generally, it involves installing kubeadm, kubelet, and kubectl on the reserved instance node, connecting the new node to your cluster by feeding it the output of a Kubernetes join command. You can create the join command from a control plane node in your cluster.

Once the join process is completed, your reserved instance will be up and running as a node in your Kubernetes cluster.

Using reserved instances on managed Kubernetes services

The process just described is how you’d use a reserved instance in a Kubernetes environment that you manage yourself - meaning you deploy the control plane and join nodes to it.

There is another type of Kubernetes deployment model - which is typically known as managed Kubernetes and is available through services like Amazon EKS and Azure AKS - where a cloud provider operates the control plane and (in most cases) manages nodes for you.

You can use reserved instances with managed Kubernetes, but to do so, you typically have to specify reserved instances when setting up node groups (which are collections of preconfigured cloud servers that you select for use in your managed Kubernetes cluster). You can’t deploy reserved instances directly because the Kubernetes management service does that for you.

Technical requirements for using reserved instances in Kubernetes

Beyond the process we outlined above for deploying reserved instances in Kubernetes, there are some additional technical considerations to bear in mind:

- Reserved instances only work in the cloud: You can’t deploy reserved instances if you create a Kubernetes cluster using on-prem or private servers, because in that case you’d be supplying servers yourself. Thus, reserved instances are only available if you host Kubernetes clusters in the cloud.

- You need to configure appropriate permissions: When creating a reserved server instance, be sure to grant permissions for your Kubernetes control plane to connect to it. Otherwise, it won’t be able to join your cluster. A server deployed in a virtual private cloud (VPC), for example, won’t be able to join a cluster if the VPC blocks network connections to the cluster.

- Kubernetes can’t differentiate reserved instances from other instances: To Kubernetes, a node is a node, no matter which type of server it is based on. This means that Kubernetes has no inherent way to distinguish between reserved instances from other types of nodes. It’s on you to make sure that reserved instances play an appropriate role in your cluster by, for example, using node taints and tolerations to control which workloads reside on reserved instances and which are on on-demand nodes.

- Reserved instances can crash: Reserved instances can fail or experience performance problems just like any other node in your cluster, hence the importance of continuously monitoring them to get ahead of performance issues. Nothing about reserved instances makes them inherently less prone to performance problems than other types of nodes.

Challenges and pitfalls of reserved instance management

While reserved instances can deliver significant cost savings, they also present some management challenges.

The greatest is the risk that you’ll end up not actually needing a reserved instance for the time period you expect, but because you committed to using the reserved instance for a specific period of time, you have to keep paying for it until the period ends, whether or not your cluster is actually using the server.

In some cases, you can end reserved instances before the committed use period ends, but you have to pay an early termination fee. In other cases, cloud providers simply don’t let you cancel a reserved instance at all; they charge you the full price of the entire commitment period, even if your server sits idle.

Reserved instances can also add some complexity to Kubernetes administration because, to use them most effectively, you need to keep track of which nodes are based on reserved instances, then use those nodes strategically within your cluster. The extra effort is worth it if it results in double-digit cost savings, but it’s still a management challenge to consider.

Best practices for maximizing reserved instance savings

To leverage the greatest value from reserved instances, consider these best practices:

- Only use reserved instances where appropriate: If you’re unsure whether you’ll need a Kubernetes node for a period of a year or more, avoid reserved instances. As noted above, there’s often not a way of getting out of a reserved instance payment agreement early, and even when you can cancel, you’ll pay extra fees to do so.

- Select the right instance type: As noted above, reserved instances come in many flavors, each with varying amounts of server resources and pricing discounts. To get the best deal, consider your overall compute and memory needs, as well as the price point of available reserved instance options.

- Consider convertible reserved instances: Some cloud IaaS services offer “convertible” reserved instance options, which let you modify a reserved instance’s server configuration during the committed use period. You still can’t cancel the reserved instance (at least not without a fee), but you have the flexibility to modify the compute and memory resources it provides. This option can be useful if you are confident that you’ll need a Kubernetes node for the long term, but aren’t certain about your hardware resource usage needs.

Label your reserved instances: Apply labels to nodes that are based on reserved instances. Not only does this help you keep track of where they are, but it also makes it easier to place certain workloads (like those that can’t tolerate disruptions) on reserved instance nodes that you plan to operate on a continuous, long-term basis.

Alternatives to reserved instances

In the cloud, the main alternative to a Kubernetes reserved instance is an on-demand instance. With on-demand instances, you pay as you go, and you can shut down a server and stop paying whenever you choose. But overall pricing is higher.

You can also use spot instances in certain circumstances, but as mentioned above, these instances can shut down without warning, so they’re really only suitable as Kubernetes nodes for hosting Pods that can tolerate sudden shutdowns.

Another potential option is what’s known as a compute savings plan. IaaS savings plans involve committing to a total amount of cloud spending over a fixed period (usually at least a year), but with the flexibility to consume different cloud servers or other IaaS resources. Thus, they would allow you to make unlimited modifications to your Kubernetes nodes, so long as your total spending on node servers meets the savings plan agreement. Savings plans are a way to achieve some of the cost benefits of reserved instances while enjoying more flexibility than you’d get from a reserved instance, although they still require a long-term spending commitment.

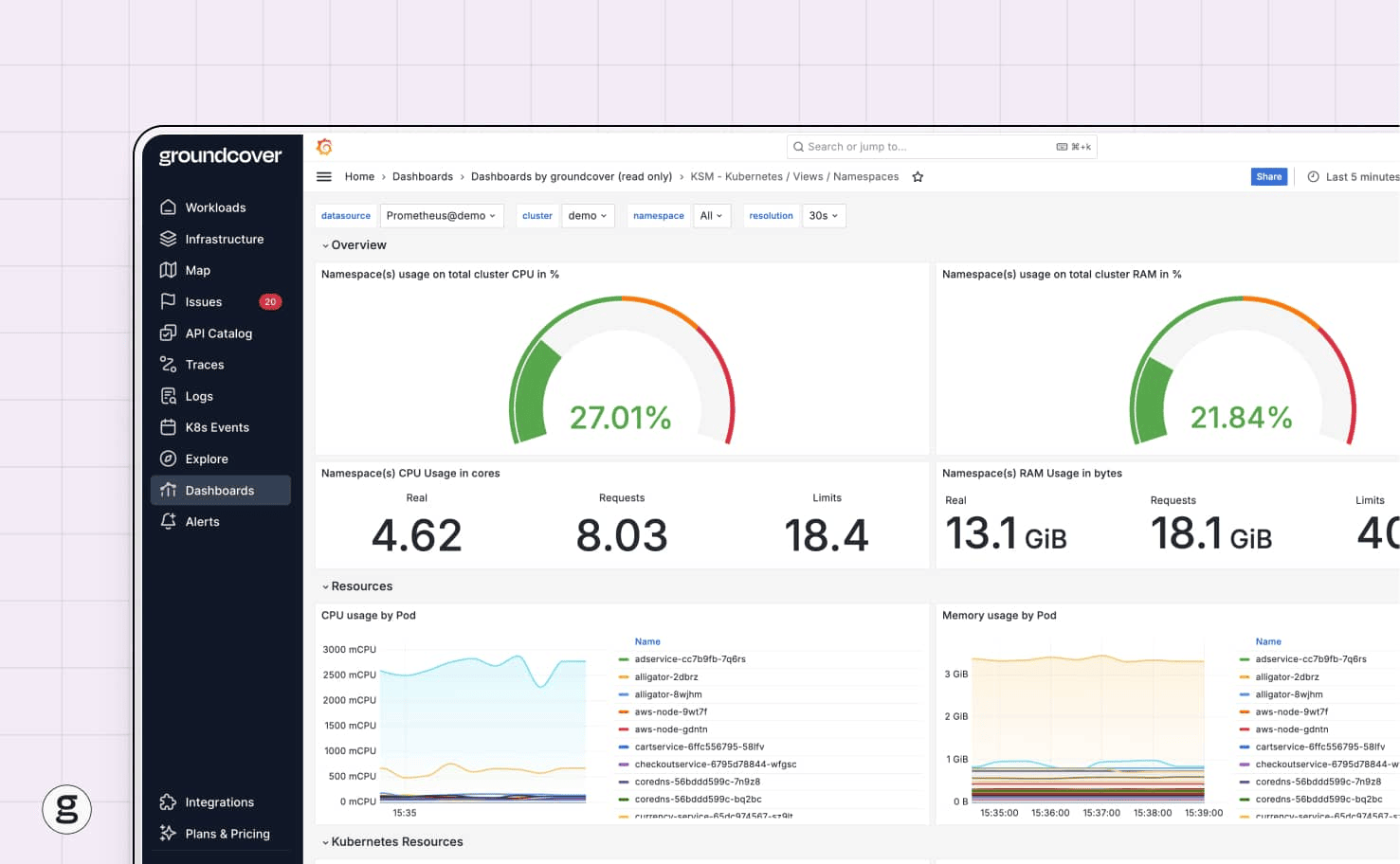

How groundcover delivers financial and operational visibility for reserved instances

The more you know about what’s running on your reserved instances, the more effectively you can use them, and the more money you’ll save in total.

This is where groundcover comes in. By delivering continuous visibility into node and Pod resource utilization, groundcover makes it easy to identify issues like underutilized nodes, which could be a sign that you’re paying for nodes you don’t need. Likewise, you can detect situations where it would make sense financially and performance-wise to move Pods from an on-demand node to a reserved instance as a way of maximizing the return on your reserved instance investment.

Winning at Kubernetes FinOps with reserved instances

Sometimes, you need the infrastructure flexibility that comes with on-demand cloud server instances. But for Kubernetes clusters where infrastructure requirements are consistent and predictable, there’s no reason to pay more for the same cloud servers. Instead, choose reserved instances, which provide the same performance as standard instances, but at steep cost discounts.

When you do this, you set your organization up for Kubernetes FinOps success, meaning the ability to optimize Kubernetes spending without undercutting performance.

FAQ

How do I track if my purchased reserved instances are being fully utilized by my Kubernetes workloads?

The best way to monitor reserved instance resource utilization in Kubernetes is via a Kubernetes observability solution, like groundcover, that displays CPU and memory usage details for each node. With this data, you’ll know whether any of your reserved instance nodes are under-utilized.

If they are, consider shifting workloads to them and shutting down your other nodes (since you can turn off other nodes without paying fees).

What is the recommended ratio of reserved instances to on-demand capacity for a production Kubernetes cluster?

The ideal ratio of reserved instance to on-demand nodes varies depending on the nature of your workloads. As a very basic rule of thumb, consider deploying enough reserved instances to cover 70 percent of your total compute and memory requirements, then relying on on-demand nodes to handle the rest.

You should also consider whether and how much you expect your workloads’ resource utilization requirements to grow over time. Investing in reserved instances makes more sense if you plan to add more workloads (or scale up existing workloads) - whereas if your overall hosting capacity will stay the same, you’ll typically have less reason to deploy a large number of reserved instances.

Does groundcover's eBPF monitoring add cost-prohibitive overhead to the reserved instances it monitors?

No. In fact, groundcover does exactly the opposite. groundcover collects monitoring data using eBPF, which is hyper-efficient because it runs directly within the operating system kernel. As a result, groundcover imposes minimal “overhead” on servers. In most cases, the CPU and memory resources consumed by groundcover for monitoring purposes are negligible, whereas with traditional monitoring and observability software, they can add noticeable loads to servers.

.svg)