Kubernetes StorageClasses:Types & Best Practices

Storage issues in Kubernetes usually show up at the worst time. A StatefulSet goes live, and the pods stay Pending, a PVC binds to an unexpected tier after a default change, or a volume can’t attach in the zone the scheduler picked.

This guide breaks down storage classes in Kubernetes. It explains what they are, how they affect provisioning, binding, and scheduling, then covers the main types, key features, and best practices for using them in production.

What are Storage Classes?

A StorageClass is a Kubernetes API object that lets cluster administrators describe the storage classes they offer. A class can represent performance tiers, backup and retention policies, or other rules the platform team wants to standardize. Kubernetes doesn’t enforce what a class “means.” It simply treats it as a named contract that points to a storage provisioner and a set of inputs for that provisioner.

Storage classes matter because they are the entry point for dynamic provisioning. When a workload creates a PersistentVolumeClaim and references a StorageClass by name, Kubernetes uses that class to decide which provisioner to call and which parameters to pass when creating a matching PersistentVolume on the underlying storage system. This is how you can expose options like a fast tier for databases and a cheaper tier for logs or backups without rewriting every app manifest around provider details.

Key components of Kubernetes storage classes

A storage class is defined by a small set of fields. Some fields decide which driver creates the volume. Others decide when provisioning happens and what Kubernetes should do with the volume when the claim is deleted.

Name and scope

The storage class name is what workloads reference in storageClassName. StorageClasses are cluster-scoped, so you can use the same class across namespaces.

provisioner

provisioner names the volume provisioner for the class. In most clusters, this is a CSI driver name. Kubernetes uses it to route provisioning requests to the right implementation.

parameters

parameters is a key value map passed to the provisioner. The keys are provisioner-specific. This is usually where you express tier behavior through driver settings, such as disk type, filesystem defaults, or encryption options, depending on what the driver supports.

reclaimPolicy

reclaimPolicy controls what happens to dynamically provisioned PersistentVolumes when the claim is deleted. Delete removes the underlying volume. Retain keeps it so that an operator can recover data or handle cleanup manually.

allowVolumeExpansion

allowVolumeExpansion controls whether PVCs using the class can be expanded by increasing the requested size. Expansion is about growth. It isn’t a mechanism for shrinking a volume.

volumeBindingMode

volumeBindingMode controls when binding and provisioning happen. Immediate can provision as soon as the PVC is created. WaitForFirstConsumer delays provisioning until a Pod exists, which helps Kubernetes provision the volume in a topology that matches where the Pod is scheduled.

mountOptions

mountOptions defines mount flags that apply when Kubernetes mounts the volume. Kubernetes doesn’t validate these options upfront, so unsupported or invalid options show up later as mount or provisioning failures.

allowedTopologies

allowedTopologies restricts where volumes can be provisioned by limiting eligible topology domains. This is commonly used to constrain volumes to specific zones or regions in clusters that span multiple zones.

Default class marker

A StorageClass is marked as default using the storageclass.kubernetes.io/is-default-class annotation. You will see how it works in a later section.

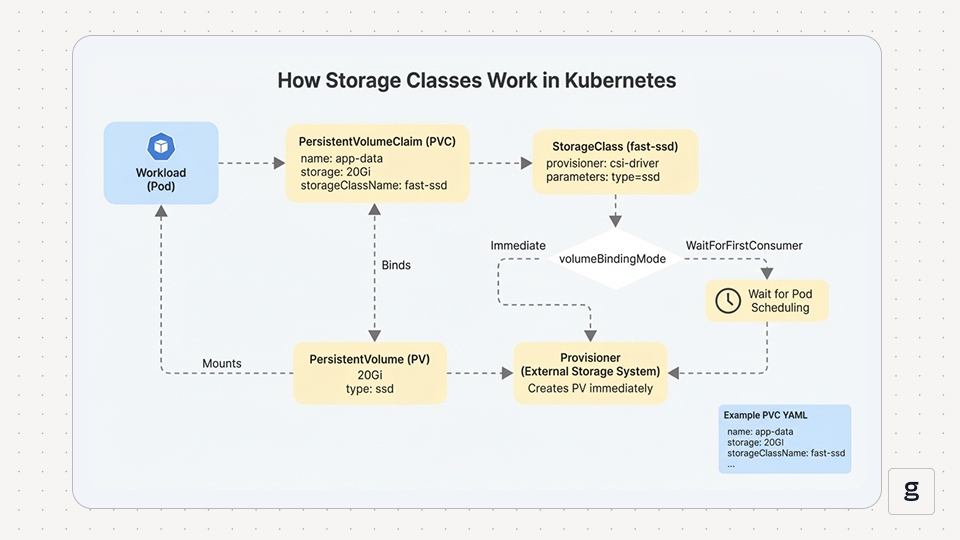

How Storage Classes Work in Kubernetes

A workload requests persistent storage through a PersistentVolumeClaim. If the claim sets storageClassName, Kubernetes selects that StorageClass, reads its provisioner and parameters, then asks the provisioner to create a matching PersistentVolume. Kubernetes binds the PV to the PVC, and the workload mounts it.

Timing depends on volumeBindingMode. Immediate can provision as soon as the PVC exists, before Kubernetes knows where the pod will run. That can create zone mismatches on topology-scoped storage. WaitForFirstConsumer waits until a pod exists, then provisions in a topology that matches where the pod is scheduled. This is why a PVC can stay Pending until there’s a consumer pod.

If allowVolumeExpansion is enabled and the driver supports it, you can expand a PVC by increasing its requested size. Shrinking isn’t supported. mountOptions apply at mount time, and Kubernetes doesn’t validate them upfront, so invalid options usually show up later as attach or mount errors.

Here is an example of a PersistentVolumeClaim:

This claim asks for 20Gi and sets storageClassName: fast-ssd. If that class’s provisioner supports the request, Kubernetes creates a PV and binds it to the claim.

Types of Storage Classes

In Kubernetes storage classes, the “type” is the storage backend and access pattern you’re choosing. A storage class points Kubernetes at a provisioner and a set of parameters. That combination drives storage provisioning when a persistent volume claim triggers dynamic provisioning, and the cluster creates persistent volumes in the underlying storage system.

CSI-Backed Block Storage

This type provisions one block volume per claim, which usually means a dedicated persistent volume for each replica. Kubernetes talks to a CSI driver, the driver creates the volume in the underlying storage system, and Kubernetes binds that persistent volume to your persistent volume claim.

Use this for workloads that need a dedicated disk, which is common for databases and other stateful apps.

On multi-zone clusters, the binding mode matters because it affects where the volume gets created. If provisioning happens before the scheduler places the pod, you can end up with a volume in the wrong zone for the node that runs the workload.

CSI Backed Shared File Storage

This type provisions shared file storage that multiple pods can mount at the same time. It still uses a storage class and dynamic provisioning, but the backend behaves like a network file system rather than a single-node attached disk.

Use this when multiple replicas need shared writes, which is common for shared content, uploads, and some build or pipeline workloads.

NFS Based File Storage

This type is network file storage exposed over NFS. Depending on your cluster and how you handle storage management, you might use an NFS CSI driver or a setup that relies on existing exports.

Use this when NFS already exists in your environment, and you want a straightforward shared file option for persistent volumes. In many setups, NFS is also a simple choice for internal tools that need shared storage without a lot of tuning.

Local Storage

This uses disks attached to a specific node. The data lives with that node, and scheduling becomes part of the storage decision because the pod has to land where the data is.

Use local storage when you want node local performance, and you accept the tradeoff that rescheduling to a different node won’t bring the data along automatically. Even though local volumes don’t support dynamic provisioning, you still define a storage class so Kubernetes can bind at the right time relative to scheduling.

Vendor and On-Prem Distributed Storage

This type is any self-managed storage platform that exposes a CSI driver and supports tiered behavior through driver parameters. In practice, you model tiers by creating multiple storage classes that map to different disk types, replication policies, or performance profiles.

Use this when you run your own storage backend. And you want Kubernetes storage classes to standardize how teams request persistent volumes, instead of having every app encode storage provisioning details in its manifests.

Default StorageClass in Kubernetes

A default StorageClass is the one Kubernetes uses when a persistent volume claim doesn’t specify a storage class. Defaulting is handled by the DefaultStorageClass admission controller. When a claim is created without a class, the controller writes the default class into the claim so that dynamic provisioning can create a persistent volume on the underlying storage system. This keeps basic manifests short, but it also means storage provisioning can drift to the wrong tier when someone forgets to set the class name.

A few edge cases matter in production. If more than one StorageClass is marked as default, Kubernetes still picks one for claims that omit a class, and it uses the most recently created default class. If the cluster has no default storage class, a claim that omits the class won’t get one, which often stops dynamic provisioning until you set storageClassName explicitly. If you need to opt out of defaulting, set storageClassName: "". Changing the default only affects new claims that omit the class. It doesn’t change existing persistent volumes or move already bound data to a new storage class.

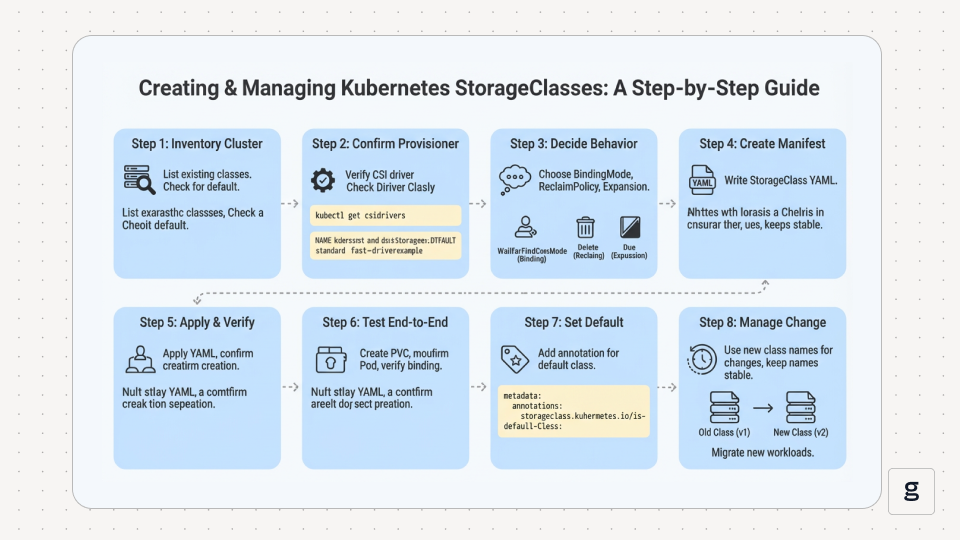

How to Create and Manage Storage Classes in Kubernetes

A StorageClass only helps if it matches what’s installed in your cluster, and you can verify the full path from a claim to a mounted volume. This section shows the exact steps to create a class, apply it, and confirm dynamic provisioning works end-to-end as shown in the diagram below.

Step 1: Inventory What the Cluster Already Has

Start by listing existing StorageClasses. Many clusters ship with at least one default storage class, and duplicating it with a different name usually adds confusion.

Pick a class whose provisioner matches the driver you have installed and whose default status matches how you want PVCs that omit storageClassName to behave.

Also, check whether a default exists and which class it is.

If you see one true, that’s the default storage class. If you see none, every PVC must set storageClassName to get dynamic provisioning. If you see more than one true, remove the default annotation from the extras so new PVCs don’t land on the wrong tier.

Step 2: Confirm the Provisioner You Are Going To Use

Your StorageClass has to point at a provisioner that is actually installed. If you are using CSI, confirm the CSI drivers registered in the cluster.

If you are not sure which driver is backing an existing class, describe the StorageClass and look at its provisioner value.

Step 3: Decide the Class Behavior Before Writing YAML

Decide the behavior up front so you don’t keep editing the same class later. Pick a binding mode that matches your topology. Multi-zone clusters usually benefit from WaitForFirstConsumer because Kubernetes can align provisioning with scheduling. Pick a reclaim policy for claims that will be deleted. Delete removes the underlying storage after the claim is deleted. Retain keeps it for manual recovery and cleanup.

Then decide whether the class should allow expansion. Set allowVolumeExpansion: true only on tiers where resizing is part of normal operations. Shrinking volumes is not supported. Add mount options only when you know the node and driver supports them. Invalid options show up later as attach or mount errors.

Step 4: Create the StorageClass Manifest

Use a single template that contains the fields you actually manage. Replace the provisioner and parameters with values supported by your driver.

If you need to restrict provisioning to specific zones or regions, add allowedTopologies. Only do this when you have a clear reason, because it can block provisioning if the topology does not match where workloads are scheduled.

Step 5: Apply the Class and Verify It Exists

Step 6: Test the Full Cycle End-to-End

Create a persistent volume claim that names the class. Then create a Pod that mounts it. This proves dynamic provisioning, binding, attaching, and mounting in one pass.

Apply it and watch the state.

If you are using WaitForFirstConsumer, the PVC can stay Pending until you create a Pod that uses it. Create a simple Pod that mounts the claim.

Apply it, then confirm the PVC is bound and the Pod is running.

Step 7: Set or Change the Default Storage Class

If you want a class to be the default, add the storageclass.kubernetes.io/is-default-class annotation to that StorageClass. Keep only one default in the steady state. Multiple defaults can change which class gets picked when a PVC omits storageClassName.

Step 8: Manage Change Safely Over Time

Treat StorageClass names as stable interfaces. If you need a new tier or a new behavior, create a new class name. Move new persistent volume claims to that class. Existing persistent volumes keep the behavior they were created with, so you avoid unexpected changes across running workloads.

Next, let's see common provisioners and what they support, because the driver behind the StorageClass decides which parameters are valid and which storage provisioning features actually work.

Popular StorageClass Provisioners

Most Kubernetes clusters rely on a small set of StorageClass provisioners. This table lists common options and the provisioner value you need to match when you create or debug a storage class.

Some environments use different provisioner values than the common defaults shown here. So always confirm the active value by describing an existing StorageClass in your cluster.

Common challenges and pitfalls with Storage Classes

Most issues with Kubernetes storage classes show up the same way. A persistent volume claim stays Pending, a pod can’t schedule, a volume disappears after a delete, or resizing doesn’t do anything.

PVC Stuck Pending

Check the binding mode first. With WaitForFirstConsumer, a persistent volume claim can stay Pending until a pod actually uses it, as you saw earlier. If a consumer pod exists and it’s still Pending, confirm the provisioner matches a CSI driver that’s installed, because dynamic provisioning can’t create persistent volumes without the driver. Also, avoid setting nodeName with WaitForFirstConsumer, since it bypasses scheduling and can keep the claim waiting.

Pod Unschedulable After Provisioning

This is common with Immediate in multi-zone clusters. The persistent volume can be provisioned before Kubernetes knows where the pod will run, which creates a zone mismatch and blocks scheduling. Switching the storage class to WaitForFirstConsumer usually fixes it. If you use allowedTopologies, keep it narrow because overly strict constraints can prevent provisioning.

Default StorageClass Surprises

If a persistent volume claim omits storageClassName, it can land on the wrong tier when the default storage class changes. Multiple defaults make this worse because Kubernetes can pick the most recently created default for new claims. If you want a claim to opt out of defaulting, set storageClassName: "".

Data Deleted or Left Behind After a PVC Is Removed

This is reclaim policy behavior. Delete removes the underlying volume when the claim is deleted. Retain keeps it for manual recovery and cleanup. Set Retain on tiers where data recovery matters, and document the cleanup process so old persistent volumes don’t pile up.

Volume Expansion Does Nothing

Expansion only works when allowVolumeExpansion is enabled on the storage class, and the driver supports it. Kubernetes supports growing volumes. It does not support shrinking them.

Mount Failures Caused by Mount Options

mountOptions are not validated up front, so bad values show up later as attach or mount errors. Some plugins don’t support mount options at all. Keep options minimal and test the storage class with a small claim before using it broadly.

When you are able to map a symptom to one of these causes, storage provisioning problems become faster to diagnose and fix.

Best Practices for Managing Storage Classes in Production

Kubernetes storage classes are easy to set up, but small choices around defaults and binding can cause noisy incidents later.

Make the Storage Class Explicit for Stateful Data

Relying on the default storage class is fine for quick tests, but it is a common source of surprises in production. Set storageClassName on any persistent volume claim that backs data you care about so dynamic provisioning always targets the intended tier, even if the cluster default changes later.

Prefer WaitForFirstConsumer When Topology Matters

If the underlying storage system is zone-scoped, WaitForFirstConsumer prevents volumes from being provisioned before Kubernetes knows where the pod will run. This keeps persistent volumes aligned with scheduling constraints like node selectors and affinity, and it avoids the “volume in the wrong zone” class of failures.

Keep One Default Storage Class in Steady State

A default storage class keeps simple PVC manifests short, but it should be deliberate. Keep a single default in steady state and treat switching the default as a controlled change. That makes it easier to reason about where storage provisioning will land when a claim omits storageClassName.

Set Reclaim Policy Based on Recovery Expectations

The reclaim policy decides what happens after a claim is deleted. Use Delete for tiers where automatic cleanup is the right outcome. Use Retain for tiers where you want a manual recovery path, then pair it with a cleanup process so released volumes do not pile up.

Enable Expansion Only on Tiers You Can Support Operationally

PVC growth works only when the storage class allows expansion and the driver supports it. Plan for expansion as a normal operation on specific storage classes, and document how your team verifies the resize and handles file system growth. Volume shrinking is not supported, so treat reductions as a migration rather than a resize.

Treat Storage Classes As Versioned Interfaces

A storage class name becomes a dependency across many manifests. When you need a behavior change that affects provisioning or lifecycle, create a new class name and move the new claims to it. This keeps existing persistent volumes stable and avoids changing storage behavior under running workloads.

With these conventions in place, you need to add visibility so you can quickly spot whether a storage issue is coming from provisioning, scheduling, or the node mount path.

How groundcover Enhances Storage Classes for Kubernetes Visibility & Control

Storage class problems rarely fail “inside” the StorageClass. They show up as a PVC stuck in Pending, a PV that never binds, or a pod that fails at attach or mount. groundcover helps by putting the signals for that whole path in one place, so you can move from a storage symptom to the workload impact and the underlying cause without bouncing between tools.

Ties PVC and PV Symptoms to the Workloads They Block

When provisioning stalls, the priority is impact. groundcover makes it easier to see which pods and workloads are waiting on a specific claim or volume, so you can focus on what’s actually blocking the rollout.

Puts Provisioning and Mount Errors Next to Events and Recent Changes

Storage failures often have a reason in Kubernetes events, with supporting evidence in logs and metrics. groundcover keeps events alongside logs and metrics, and it tracks relevant Kubernetes changes so you can line up “what changed” with “when provisioning or mounts started failing.”

Uses eBPF to Surface Node-Level Causes Without Application Changes

Many storage incidents are really node constraints or infrastructure problems that only show up at bind, attach, or mount time. groundcover uses eBPF to collect low-level signals without adding SDKs or changing application code, which helps when the root cause sits below the app layer.

Makes Full Coverage Practical With Host-Based Pricing

During a storage incident, you need the full picture. groundcover uses host-based pricing rather than data volume-based pricing, so you can keep the signals you need turned on without tuning around ingestion. The Free plan is $0 and includes one cluster and up to three users. Team is priced per host per month, and Enterprise is also priced per host per month.

With that visibility in place, storage provisioning becomes easier to reason about because you can follow the path from the StorageClass choice to PVC and PV state, then to pod scheduling and mount behavior.

Conclusion

Kubernetes storage classes control how persistent volumes are provisioned, bound, expanded, and cleaned up. Clear class definitions, deliberate defaults, and the right binding mode keep storage behavior predictable across teams and clusters. groundcover completes this setup by making the full storage path observable, from StorageClass and PVC decisions through PV binding and pod mount behavior, with the node-level signals needed to explain failures.

FAQS

What factors should determine my choice of a StorageClass for different workloads?

Pick based on access needs first. Match the workload’s access mode and sharing needs, then choose the backend type and tier that fits performance, expansion, and data lifecycle requirements like reclaim policy.

How do existing PersistentVolumeClaims behave when I change the default StorageClass in a cluster?

Existing bound PVCs don’t change, and their persistent volumes don’t move tiers. The new default applies to new PVCs that omit storageClassName. PVCs with storageClassName: "" won’t get a default assigned.

How does groundcover help monitor or enforce StorageClass usage and storage-tier compliance in Kubernetes?

groundcover makes StorageClass and PVC behavior visible by correlating events, logs, metrics, and workload context, so you can quickly see which workloads are using which classes and where provisioning or mounts are failing. It doesn’t enforce policy by blocking manifests, but it makes drift and noncompliant usage easy to spot and alert on.

.svg)